How the Army plans to use Microsoft's high-tech HoloLens goggles on the battlefield

Todd Haselton |

I'm inside a Black Hawk helicopter flying from the Pentagon to Fort Pickett, Virginia.

I'm flying with Under Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy and Command Sgt. Maj. Michael A. Crosby, who are explaining how Microsoft's technology will be used to better train soldiers and make them more effective in the real world. Soon, I'll see for myself.

Todd Haselton | CNBC

We flew in Black Hawk helicopters with the Army.

I also spoke with a few special operations soldiers, who spent the previous two weeks at Fort Pickett testing the new headsets for the first time.

The headset is impressive — better than any augmented reality experience I've ever seen, including

Magic Leap, which also tried to win the Army contract. The project is also a showcase for the Army's plans to work more closely with America's tech companies to speed innovation in military.

For decades, anyone who wanted to win a military contract had to jump through hoops in a process that could take five to seven years just for the military to decide what it wanted. It would sometimes take 20 years for a product to hit the field, according to the Army. And the process rarely involved the troops who actually ended up using that technology.

A lot has changed.

There's a new Futures Defense Command based in Austin, Texas. It allows tech companies, from small start-ups all the way up to America's biggest firms, to work directly with the military's leadership and soldiers to bring new technology to the battlefield.

CNBC

Microsoft launches HoloLens 2 at Mobile World Congress in Barcelona

To be clear, the military is only just beginning its work on these headsets, so the Army didn't allow us to video or photograph them ourselves and instead provided us with a batch of images we could use. "The technologies being developed and tested are rapidly evolving," the Army explained.

But I was able to wear a modified HoloLens 2 headset to see an example of the software experience the Army has in mind, and we simulated the experiences here. I also learned how it's working with tech companies to quickly fine-tune existing technology to what it needs on the battlefield.

Here's what the Army's new headset is like.

The Integrated Visual Augmentation System

US Army

Soldiers wearing the IVAS system, a modified version of the HoloLens 2.

The military calls its special version of the HoloLens 2 "IVAS," which stands for Integrated Visual Augmentation System.

It's an augmented-reality headset, which means it places digital objects, such as maps or video displays, on top of the real world in front of you.

Several companies are betting big on AR as the future of computing, since it will allow us to do much of what we can on a computer but while looking through glasses instead of down at a phone or at a computer screen.

Apple,

Google and Magic Leap are all building AR-capable software and hardware.

I put the headset on and pulled it down so that my eyes were peering through a glass visor. That visor is capable of displaying 3D images, information, my location and more. IVAS isn't nearly finished — I was using a test unit — so it was a bit buggy and had to be restarted once during my demo.

US Army

Soldiers wearing the IVAS system, a modified version of the HoloLens 2.

When I first put it on, I saw a map in front of me that showed exactly where I was. It gave me a birds-eye view of the building I was standing in and also showed a nearby building. It's like any satellite image you can find online.

But as I turned my head, a small arrow icon representing my location also turned. I could also see several other dots representing my other "squad members" who were also wearing the headsets.

Kyle Walsh | CNBC

A CNBC render of the sort of map a soldier could see if they looked down.

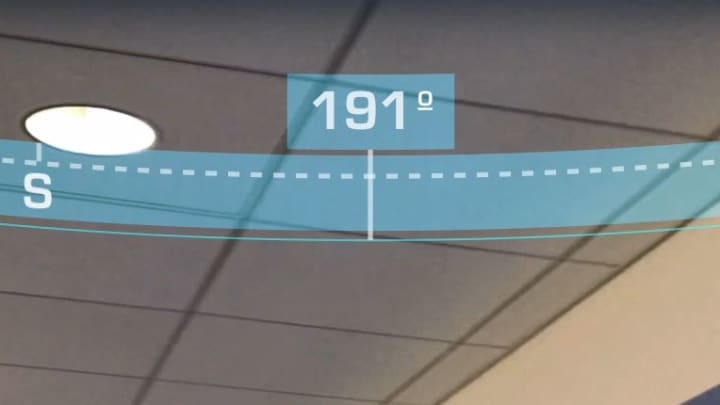

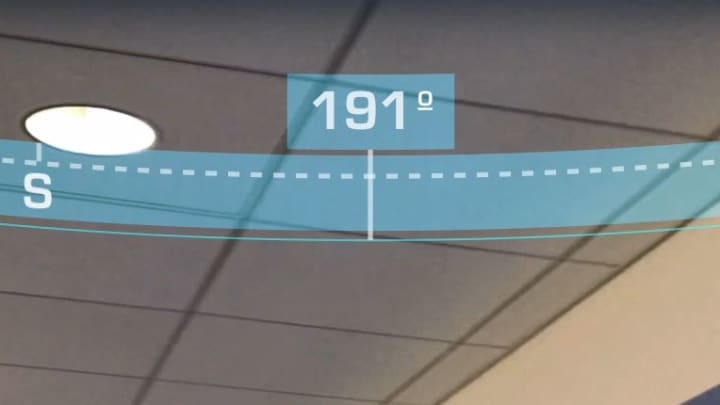

The army said it learned from early testing that soldiers might find this map distracting, in part because it isn't see-through when active. So it also included a compass I could see by looking up.

As I moved, I could see different waypoints marked at different degrees. A soldier could use this feature to locate members of his squad are or a known enemy position.

Kyle Walsh | CNBC

A CNBC render of the compass a soldier might see insight IVAS.

If this sounds familiar, you might be a gamer. The whole experience felt natural to me, as I've played lots of first-person shooter video games that show me exactly where I am on a map, where my teammates are and where the enemy is. It was almost like a real-life game of "Call of Duty."

But IVAS goes even further. It can also be used for thermal imaging.

Kyle Walsh | CNBC

A CNBC artistic rendition of the thermal night vision capabilities of IVAS.

Night vision goggles currently used in the field emit a green glow, which the enemy can see. IVAS doesn't glow as much, and still allows soldiers to see other people in the dark.

When I tried it, people glowed bright white, as if everyone in the room had suddenly turned into ghosts. With the lights off, I could see someone standing plainly behind a set of ferns, which I wouldn't have been able to see otherwise.

McCarthy explained, "With current night vision, smoke can blur what you see. With thermal, you can see through the smoke and engage and destroy a threat. This is a game changer on the battlefield," he said, noting that Russia, China and other potential adversaries that know about these capabilities "will not want to engage us."

You might also wonder, as I did, how a soldier can aim a weapon while wearing IVAS. Cleverly, the system shows the reticle, or the aim from the weapon, right through the visor.

U.S. Army

An example performance report of what soldiers will see through HoloLens after a training exercise.

The military will also use IVAS beyond the battlefield.

"It's not just for use in combat," McCarthy said. "We can gather data on a soldier in training and improve their marksmanship. We can see their heart rate."

For instance, in a training facility where soldiers run through rooms and clear them of virtual enemies, the command can see exactly what they were looking at when they entered. After the exercise, soldiers gather around a circular black table and watch a report of their performance on IVAS.

The current iteration of IVAS is too large to work with helmets, but the Army is trying to make it much smaller. One Army leader said he expects the size to be like a pair of sunglasses within six months. (Tech companies like Facebook have also predicted AR glasses will eventually shrink, but they say that'll take years, not months.)

Andrew Evers

Microsoft's new HoloLens 2 augmented reality headset

While Microsoft is the big-name tech partner, Mark Stephens, director of acquisition and operations for IVAS, told me that 13 companies won contracts for the system.

One of those companies, Flir, has a thermal sensor stuck right on the front of the modified HoloLens 2. It looks like half of a silver pinball. This is what provides the night-vision capabilities and more.

"There are 12 sensor contracts," Stephens said, noting that another unnamed company is helping to turn 2D graphics inside HoloLens into 3D images.

Stephens also explained why the Army picked Microsoft over companies like Magic Leap, which were also bidding for the contract.

"We need to iterate often and we found a partner with Microsoft that does that," he said. "It's abnormal that a vendor has direct input from soldiers for like two weeks."

But the Army has been watching this tech for a while.

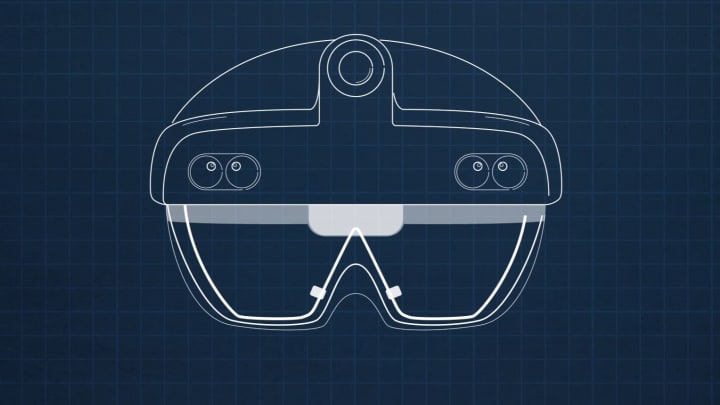

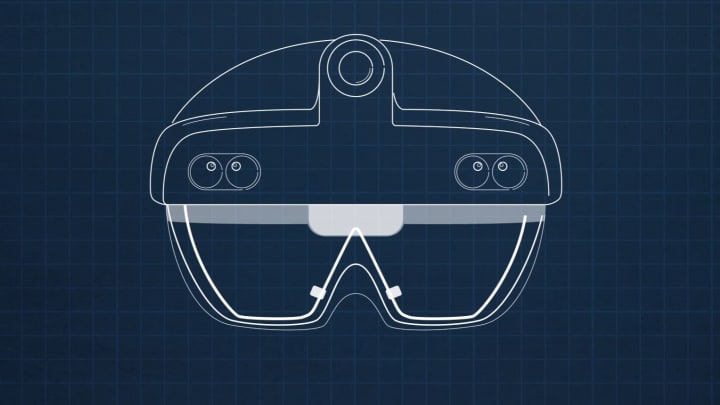

Kyle Walsh | CNBC

A CNBC sketch of the IVAS model we saw at Fort Pickett.

"We've been monitoring virtual and mixed reality and sensor miniaturization," Stephens said. "Several companies were evolving into an individual form factor," he said, referring to the helmet-like device.

McCarthy and other senior leadership briefed former Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis on the potential use cases for augmented reality in May. Mattis saw video of potential uses for augmented reality, and eventually approved the Army to pursue using it. Microsoft won the contract in November.

The Army will work exclusively with Microsoft for the 24-month duration of the contract, which means other tech companies working on AR, like Google, Apple or Magic Leap won't have a chance to make another bid for now, Stephens said.

What America's most elite soldiers think about IVAS

Magdalena Petrova | CNBC

A member of the Army's elite special forces group who has been testing IVAS.

I spoke with three elite special forces soldiers who had spent the previous two weeks at Fort Pickett using IVAS for training in five-man teams. They did this to test the system and to provide feedback to Microsoft and the Army on how the headsets can be improved. The Army asked that we not use the soldiers' names to protect their identities.

The soldiers said they were happy to finally get some technology upgrades to their equipment.

"It's common for us to have multiple systems that do an aspect of what the IVAS is doing itself," one soldier said.

The soldiers said they were excited about "after-action" reports, which showed them a summary of their accuracy and performance after a training exercise. "This system is next-level for training and for the future of Marines," one soldier said.

U.S. Army

An example performance report of what soldiers will see through HoloLens after a training exercise.

The soldiers kept referring to IVAS as a "combat multiplier" which, in short, means it makes them more deadly. This is particularly important for training ahead of deployment.

"Whatever we do on the ground plays off of what we do in training for real-time missions and the real world," one soldier said. "We might not know what [the battlefield] looks like, but we can predict and take Google images and implement that into the IVAS. It's a huge boost to rehearsal."

U.S. Army

An example performance report of what soldiers will see through HoloLens after a training exercise.

"The engineers and scientists are side by side," Command Sgt. Maj. Crosby told me back in the helicopter. "So if there's a gap that needs to be adjusted, they take it back to the lab, and back in soldier command until we get it right."

U.S. Army

An example performance report of what soldiers will see through HoloLens after a training exercise.

The military has been working on this version of IVAS for only a few months, and soldiers have just started to provide real-world feedback. We won't see the current model on soldiers' heads right away since a lot still needs to change, but it won't take long.

McCarthy said he expects to begin "fielding it to thousands and thousands of soldiers across the force" as soon as 2022 and 2023.

"As soon as the technology is solidified and ready for the war fighter, we're ready to roll it out," Crosby added, suggesting it could roll out more broadly by 2028.

Comments

Post a Comment